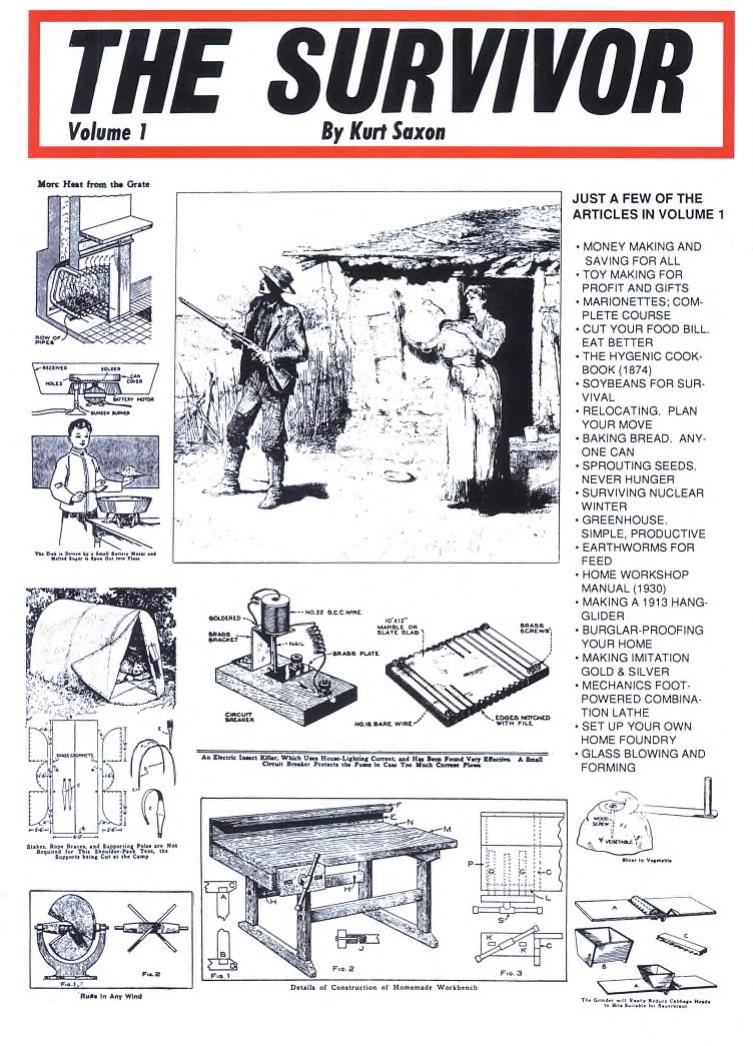

Today's excerpt begins on page 136 of The Survivor Volume 1.

By MARTIN DONNELLY

There was no mushroom cloud.

Nothing exploded, or crashed.

There was no dramatic detonation, thunderclaps did not occur nor did the heavens open, rivers kept their banks.

The telephone dialing systems continued to click automatically, the electric lights burned.

Nobody knew, at first, that anything was happening.

I didn't know either.

I'm an old man, and old men are supposed to be full of wisdom, but I was no wiser than anybody else that day.

I dozed comfortably in my armchair, secure in the certainty that my granddaughter would be home soon to fix my supper.

And she was, and she did.

Nothing was happening.

But it had begun to happen, and I began to learn that it had.

The next morning Mrs. Phillips, our neighbor, came to borrow some aspirin for her arthritis because the drug store had unaccountably run out of it.

That evening my granddaughter was late in getting home from work because her regular bus had never showed up and she had had to wait for another.

My favorite television program was replaced by an old movie.

As we were getting ready to go to bed, the lights flickered two or three times.

I began to get a feeling in my old bones that something was going wrong.

But it all took place very gradually.

So slowly that no one was alarmed at first, me included.

Life went on.

It was only that everything slowed down.

Mrs. Phillips never did get any aspirin from the drugstore.

My granddaughter began to ride her bicycle to work because she couldn't depend on the bus.

There was an announcement on the radio that because of a temporary power shortage all radio and television stations would go off the air at nine o'clock in the evening.

On the third day my granddaughter came back home an hour after she had left for work and said.

"There’s nobody at my office.

The building is locked up and I couldn’t even get in.“

While we were talking about this, Mrs. Phillips came to the door and said.

"May I use your telephone?

Mine is out of order and I have to call my doctor.

My arthritis. . ."

But our telephone was out of order too.

And at last my old brain, clogged though it was with age and torpor, began to function.

I began to add things up.

The commodity distribution system failing.

Power going out.

Communications cut.

It was all coming apart.

Not dramatically, gloriously, in one big blinding flash.

Slowly and grindingly.

The system was creaking to a stop.

There had come to be too many people, we were all of us too greedy, we had scourged the earth of its good things, taken the ton off of life and called it civilization, forgotten that the essence of living is simply surviving.

I said to the two women.

“Pack up.

Take what you can carry.

We are leaving here."

They looked at me incredulously but they moved.

I went to the basement and got my survival equipment.

It was pitifully inadequate and I was ashamed of myself for having left it lying there for ten years unchecked.

It wouldn't be much use.

I was afraid.

I had myself become complacent, lulled into thinking that it wouldn't really happen in my lifetime.

But now it had happened.

Now an old man had to try to begin to live again, with whatever tools he had or could find or could make.

We went to the ranch, and had just enough gas in the pickup truck to make it.

We walked from there to the cave.

I was pleasantly surprised to find that the sleeping bags so long in storage were still comfortable and warm.

And, the next morning, that canned dried fruit and undehydrated coffee made a good breakfast.

But I was feeling a growing sense of hopelessness just the same.

At I looked at the supplies in the cave I found them pitifully inadequate, and cursed myself at not having added to them as I had planned to do.

Moreover, I had only the two women to help me carry what we had to the lake over the mountain.

My granddaughter Cynthia was a good girl but frail.

Mrs. Phillips was almost as old as I.

We had to try, though, I made up packs for us all, thinking disconsolately that I would have to come back at least twice more, and we set forth.

It took us until four in the afternoon to get over the mountain and down into the valley, and when we got to the lake my chest was hurting.

There was good news.

Cynthia cried.

"Oh. look!

The Wilsons are here!”

And indeed the Wilson family was there waiting for us, having come over the ridge on the other side of the lake.

There was bad news: they were standing there, two adults and four children, with the clothes they had on their backs and nothing else.

"Hijacked." Rob Wilson said bitterly.

“They took our truck and didn't even bother to shoot us."

More bad news: the portable generator I had stowed under the floor of the cabin was ruined.

My fault: I hadn’t packed it properly, hadn't been there to check.

The packing had been chewed away by varmints, and what was left was a corroded mass of copper.

No power.

No radio.

No pump.

The next day we scored a modest success, in that Rob Wilson and I made it to the cave and brought back more than half of the remaining canned goods.

But the next day Rob sprained his ankle going down the mountain, and I had to leave him to hobble back while I went on alone.

To see the smoke from the burning ranch house.

And to make a mistake.

Thinking they had not found the cave, I went in.

There were two men there.

The big bearded one said.

“You're not going to try to shoot us, are you?

Dad?

With that scattergun you've got hung on your shoulder?” and raised his rifle.

No.

I wasn't going to try to shoot them with the 12-gauge slung over my shoulder.

I shot them with the .44 Magnum I drew from my belt.

I had handloaded the cartridges myself, and a little loo hot; the concussion in the confined space of the cave nearly collapsed my eardrums.

The 240 grain slugs from the Model 29 blew holes the size of golf halls in the chests of the two men.

I emptied the contents of my stomach on the floor of the cave at sight of what I had done.

There was no strength in me to pack the other supplies I had meant to get.

I only managed to snatch the hand-cranked radio transmitter from where I had hidden it.

The effort of stepping over one of the bodies to get the radio was almost too much for me, and I left the cave empty handed otherwise.

The trek back to the lake was a nightmare I scarcely remember.

When I got there at last my chest was on fire.

I knew finally that I was an old man and useless.

Everything I had done had been wrong.

I had not prepared properly for survival, and neither I nor any of the people who had trusted me would survive.

And I had killed two fellow human beings, no matter what manner of men they were.

I had failed.

Dimly I remember that Cynthia looked anxiously at my gray face and heaving chest, and guided me stumbling to my sleeping bag in the cabin.

After that, consciousness was like a flickering candle and I lost all track of time.

Cynthia was always there.

Mrs. Phillips, too.

I remember seeing Rob Wilson leaning on a cane once or twice; he brought with him a small boy who looked at me with round eyes and said, “Don't be sick any more, please get all well."

I still find it hard to believe that a full week passed before I became fully aware again.

But Cynthia told me so.

She was looking healthy and fit and not frail at all.

Even more astonishing, Mrs. Phillips was there too and seemed to have grown twenty years younger.

And there was a young man with a doctor's stethoscope around his neck.

They were all smiling at me.

"Look out the window," Cynthia said, helping me to sit up.

"See what we got after we cranked up the radio you brought."

I looked out the window.

There were people everywhere, all busy doing things.

A helicopter stood at rest by the shore of the lake.

There was a truck— I wondered how it had got there until I saw the new corduroy road it had traveled— and men were unloading things from the truck.

Two small prefab buildings were going up nearby.

Out of the corner of my eye I saw that Mrs. Phillips was approaching and holding out a bowl of soup, and smiling at me.

I could smell the soup and it smelled good.

I would eat it with pleasure, I knew.

But for the moment I turned my eyes back to look out the window.

I wanted to see everything while I still could.

For despite all the smiling faces around me.

I knew that I was an old man and that the fluttering sensation I now fell in my chest would grow and grow.

What I wanted to see out the window, what I took a dying man's final joy in seeing, was the beginning of a new civilization.

What I saw was survival.

Kurt Saxon thought civilization would have collapsed by now.

He spent the majority of his life collecting knowledge of home based business.

His goal was for all his readers to survive at a more comfortable level than those that were less provident.

He knew the importance of communicating at a level folks could understand.

Most of what he has compiled for our benefit can be easily understood by everybody.

He also includes a subtle sense of humor.

You can find the majority of his life's work here.

Hear him read his stories.

Posts with rewards set to burn only burn the author's portion of the rewards. Curators still get paid.

IF you think this content should be eligible for rewards from the content rewarding pool, please express your discontent in this discord: